Please read the first section of this post via the below link:

Start of the Assassinations

Surrounded by more powerful adversaries and seeking a new method of achieving their aims in lieu of an army, Hasan’s Nizari began to utilize another strategy that had been used by Shia

groups for centuries – assassination.

Though political murder was and is a universal method of warfare, the Nizari granted it an increasingly central role in their politica strategy, knowing how effective it could be.

This part of Nizari history has been distorted by groups who were hostile to or unfamiliar with them and their practices. For example, rumours circulated by later Latin sources threw the term ‘Hashashin’ around to designate them, due to the probable fiction of Hashish use as inspiration for the assassins.

That being said, there does seem to have been what might be called a ‘cult of assassination’

in Alamut and the other fortresses.

Nizari Assassins

Nizari assassins were known as fi’dai – literally ‘those willing to sacrifice’ – and were revered for their bravery and courage. This was largely because such missions were considered suicidal. Nizari leaders dispatched their fi’dai, who became increasingly professional, primarily to dispatch targets who were a known threat to the Nizari State.

This included Seljuk viziers, local emirs, and prominent rulers.

The Nizaris also managed to expand their influence into Syria around the time of the First Crusade, capturing a few fortresses and intermingling politically with Seljuk principalities and

the Christian crusader states.

In Persia, Muhammad Tapar took command of the Turkic empire in 1105 and immediately launched a series of campaigns against all of the Nizari territories south of the Caspian Sea.

His main stroke fell on Shahdiz in 1107, which fell relatively quickly after a fi’dai failed

to slay one of the sultan’s viziers.

For over a decade, Seljuk campaigns against the Nizari continued unabated, resulting in constant massacres and persecution of those Ismaili who could not escape to the castles.

Many Nizari fortresses fell under the assault, but finally, when the Seljuks were on the

verge of taking Alamut in April 1118, Muhammad Tapar died and the pressure waned.

New Phase in Nizari-Seljuk Relations

This was the beginning of a new phase in Nizari-Seljuk relations – one of a stalemate due to exhaustion.

Scores of Ismailis had been slain in the cities, damaging their support base. Hasan’s three-decade-long anti-Seljuk revolt, in which a ‘state’ with no real army had survived, inflicting

damage on a giant military empire, had failed, but the Nizari state was still a cohesive

one.

From that point, the focus would turn to defence and consolidation – the transformation

of the Nizari state into a permanent one. Hasan’s attention turned to scholarly pursuits

and peaceful relations, though the latter was often achieved by illicit means. For example,

Hasan received reports that a Seljuk ruler named Ahmad Sanjar was planning a campaign

against him. Allegedly, that man woke up one day to find a dagger thrust into the bed next

to him, accompanied by a note stating that Hasan-i Sabbah would like peace.

Shocked and no doubt slightly terrified, he gave the Nizaris no further trouble, even promoting a relatively tolerant attitude and granting them 4,000 dinars per year as a pension.

The threat of assassination clearly worked as well as the deed itself, at least for as long as Hasan was alive. However, the Nizari leader fell ill in 1124 and designated his successor, appointing a council of advisors to guide him in the role. In the same year, he passed away inside Alamut at the age of 70, having never left the citadel for thirty-four years.

Assassins After Hasan Sabah

An effective stalemate continued for decades following his death. Often the Nizari in Persia or Syria would take a fortress, only to have another one taken from them.

There were periods of peace as well as those of intermittent warfare. Throughout all of it, the strongholds of Hasan’s movement remained cohesive and organised.

Rashid al-Din Sinan

In 1162, a man named Rashid al-Din Sinan was sent from Persia to lead the Syrian branch of Nizari, who had grown in influence in the half-century since first penetrating into the region. Despite being far removed from one another territorially, the various Nizari enclaves all took their orders from the central leadership in Alamut.

This appointee would later become known as the Old Man of the Mountain in the tales of European explorer Marco Polo.

Sinan immediately delved into the ever-shifting, interfaith web of political alliances in Syria,

eventually sending fi’dais to assassinate an up-and-coming Muslim leader who sought to unify the region – Saladin.

The Nizari killers failed twice, once after invading the Ayyubid ruler’s military encampment

and once during his siege of Azaz.

Sinan’s headquarters at Masyaf was besieged in response, but it did not fall, and a compromise was eventually reached between the two great men.

Sinan and the Third Crusade

One of most notorious assassinations of Sinan’s rule occurred during the closing stages of the Third Crusade.

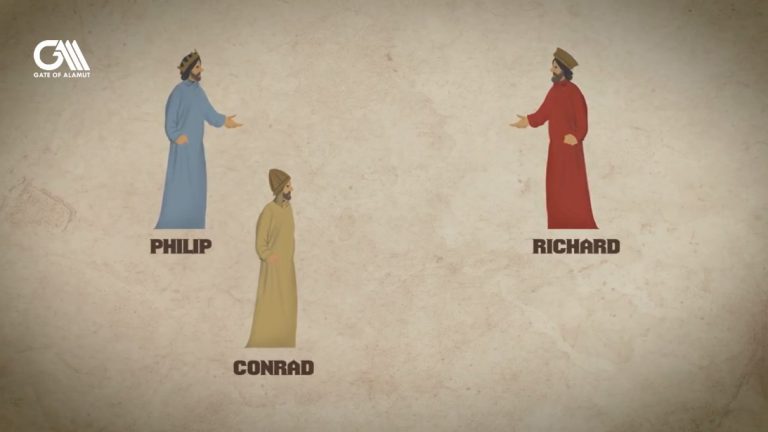

A rivalry had existed between Philip Augustus and Richard the Lionheart since the venture’s early stages, which prompted both men to support different candidates for the crown of Jerusalem.

Much to King Richard’s anger, the highly competent Conrad of Montferrat was unanimously elected to the throne of Jerusalem.

However, the prospective monarch would never be crowned.

At noon on April 28th 1192, the Frankish crusader lord was returning from having lunch with his friend – the Bishop of Beauvais – accompanied by a few guards.

On his walk, Conrad was approached by two Christian monks whom he had become familiar

with recently.

A conversation began between the two groups, putting Conrad’s guards at ease with the seemingly innocuous men.

At that moment of greatest vulnerability, they suddenly sprang forward with daggers,

brutally stabbing the king-elect with at least two blows to the side and back.

Although the assassins – who were fi’dai dispatched by Rashid al-Din Sinan – were either

killed or captured, Conrad either died instantly from his wounds or soon after being taken

to a nearby church.

Various motivations and culprits have been designated for the murder.

Richard the Lionheart was accused because of his enmity towards Conrad, while a letter

to Austria’s Leopold V detailed Conrad’s murder of a shipwrecked Nizari crew in Tyre

as the cause of his death. Whatever the case, this killing only furthered the mythical European

vision of mysterious assassins who did not fear death.

These later decades of the twelfth-century marked a high point of the Syrian Nizaris

in particular, a period that came to an end when Rashid al-Din Sinan died at Masyaf in

13th century for the Assassins

The thirteenth-century was dawning, and it would be the equivalent of an apocalypse

for the Ismailis.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the Mongol juggernaut rolled through the Islamic

world, crushing all in its path.

The khans became famous for their utilization of talented native peoples from the lands they conquered, and this apparently included a number of Sunni courtiers, who despised the Ismaili. They must have known of the Nizari’s reputation for defiance, in addition to their penchant for assassination.

Perhaps after adding a few more fanciful details, these tales must have greatly concerned the khan, who viewed them as a risk.

The Assassins and the Mongol Khan

After initial lukewarm relations, Muhammad III of Alamut received a dreadful shock in

- Upon the ascension of Ogedei’s successor Guyuk, many Muslim leaders sent embassies

of congratulations and gifts to the great khan.

Out of them, only the Nizari ambassadors were harshly dismissed. To back up this hostile

stance, the khan proclaimed that of every ten reinforcements he would send to Persia,

two must be used to reduce rebellious lands, prominently those of the Ismaili.

This was a policy that Guyuk’s successor Mongke, who desired complete and total domination

of western Asia, mimicked.

Despite offering ferocious resistance, the Mongol pressure was simply too great. On November

19th 1256 the final Nizari imam – Khurshah – surrendered Alamut to Hulagu and was initially

shown mercy.

After being escorted from his lands, however, he was unceremoniously killed

in the Khangai mountains.

Fall of Alamut

Back in Persia, the walls of captured Nizari fortresses were torn down, vast libraries of knowledge were torched and thousands of civilians slaughtered.

One by one the mountain strongholds fell, with their fi’dais putting up a desperate

fight.

The final Ismaili castle of Girdkuh fell on December 15th 1270. The violent destruction of Hasan-i Sabbah’s Alamut-based state put an end to Nizari statehood forever.

Nizari Ismailis Today

Against all the odds, the Nizari did survive into the modern-day and are currently led by their 49th imam – Aga Khan IV – from the Portuguese capital of Lisbon, with an estimated 15 million followers in more than 25 countries.

Although these Nizaris are far less militant, the story of self-sacrificing predecessors continues to shine brightly in their memories.

All the credit of this post belongs to the following youtube post:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vG8qmlKdRjs

I am Hosein Farhady, a specialized guide for the Assassins Castles and the history of the Ismailis in Persia.

If you are ready to book an Alamut Tour with me, you only need to touch the whatsapp or email icon at the bottom of this page. Or go to the contact us page.

Pingback: Qazvin Caravanserai - Gate of Alamut

Pingback: Armaan in Alamut Valley - Gate of Alamut