Conception of an “Assassin”

Many men and women of violence have been romanticized by people of later eras.

Driven by pieces of popular culture such as the Assassin’s Creed games, the popular conception of an “Assassin” has turned from that of a “ruthless murderer” to that of a “renegade antihero”, killing only because it is for the greater good.

The foundations of this viewpoint lay within the historical Islamic realm which would come

to be known as the Nizari Ismaili State. I will explain that how the Nizari became the most feared assassins of their era, and how they eventually met their end.

Sunni Vs Shia

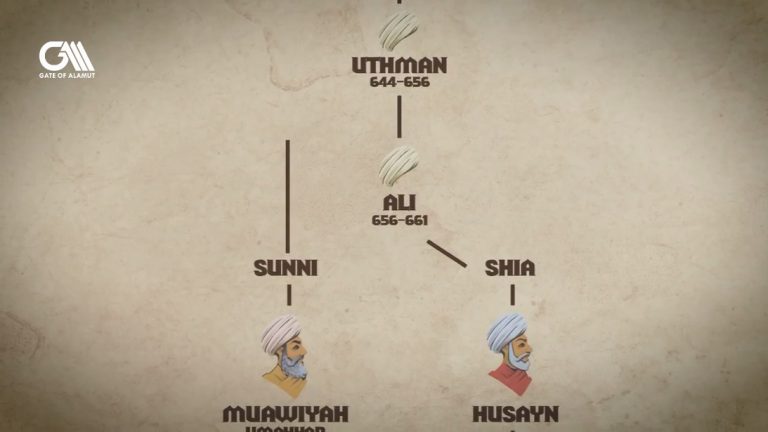

Almost simultaneously with Islam’s meteoric rise to superpower status in the seventh-century,

internal division permanently split the new faith into two opposing parties.

These were the Sunni – Muslims who believed that Abu Bakr’s succession of Mohammed in 632 was correct – and the Shia – who considered the prophet’s cousin and son-in-law “Ali” the legitimate heir – or ‘Imam’.

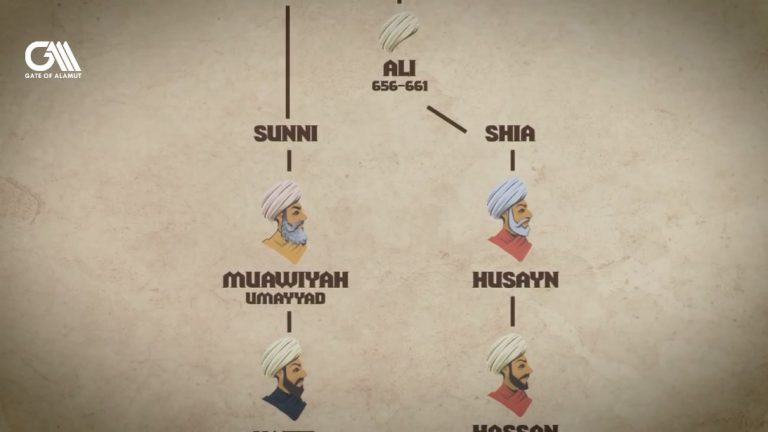

After a series of civil wars, Umayyad leader “Muawiyah” took the caliphate from the heirs

of Ali, and this subsequent struggle against central power defined the Shia and prompted

the breakaway of many subgroups with diverging viewpoints.

In time, the Umayyads were defeated by the Abbasids in another civil war.

The Foundation of Ismaili Sect in Shia

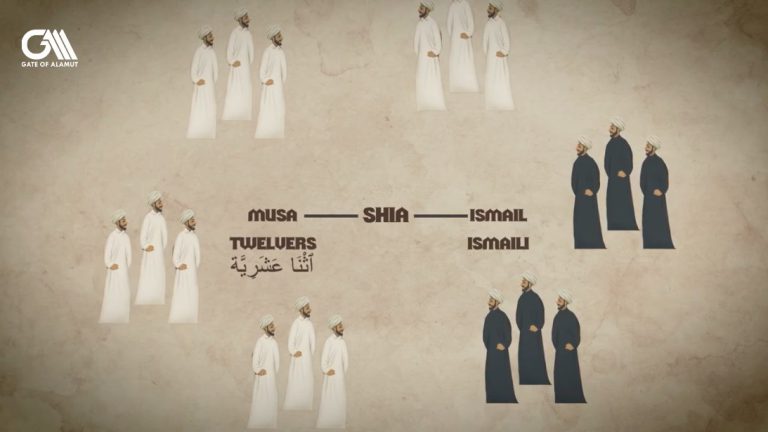

The age of Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur was the catalyst for one of these new sects – the Ismaili. At some point in his reign, the sixth Shia Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq declared his radical eldest son Ismail to be his divinely inspired successor – a doctrine known as “nass”.

However, his plans were derailed in 762 when Ismail unexpectedly died at the age of 40, raising hard questions on who the next imam should be.

When Ja’far also passed away a few years later, six groups disputed who the next Imam ought to be.

Two of these groups became the first Ismaili Shia by asserting the legitimacy of Ismail despite his death, and supporting his descendants.

In contrast, those who accepted Ismail’s younger brother Musa’s imamate, eventually became known as ‘Twelvers’, the Shia denomination championed by the Iranian states, from the Safavids to the modern Islamic Republic of Iran.

The Ismailiyah disappear from history until around the mid ninth-century, when their leaders

burst onto the historical stage and spread the movement to regions across the faltering Abbasid caliphate, from the Maghreb to Khurasan.

The movement managed to tear away vital pieces of the once unified Caliphate.

An Ismaili revolt in Arabia led to the creation of a ‘religious-utopian republic’ in modern Bahrain under the Qarmatian dynasty, whose slaveholding society was otherwise unusually egalitarian and communal for the age.

However, the crowning achievement of this sectarian revolution was the establishment of al-Mahdi Billah’s Fatimid Caliphate in North Africa.

Ismaili Century

Although the Fatimids only occupied a relatively small and peripheral area at first, they managed to hugely increase their power in 969 by conquering Egypt.

Bolstered by that, the Fatimids entered what historian Farhad Daftary dubbed the ‘Ismaili century’.

In the hundred years following Egypt’s fall to the Shia, rich and diverse Ismaili literature flourished in the many new libraries, blended with other traditions, and resulted in incredibly complex systems of thought.

The Fatimids developed complex administrative and financial structures, in addition to re-establishing far-flung trade routes to India.

Along with the accompanying riches and exotic goods, this exchange also spread Ismaili teachings to Gujurat.

Fatimid on the downhill

However, beginning in the second half of the eleventh century, the Fatimid star began to fade, as the Shia caliphate was faced with internal and external problems.

A dynastic crisis shattered Ismaili unity forever in December 1094, when Fatimid Caliph

al-Mustansir passed away.

Nizar vs Al-Musta’li

After a 58-year-long reign, it was widely expected that his well-prepared fifty-year-old son – Abu Mansur Nizar – would inherit the throne in Cairo.

But the powerful vizier – al-Afdal – effectively controlled the government, and wanted to retain personal power.

Upon al-Mustansir’s death, al-Afdal organized a palace coup, placing Nizar’s inexperienced 20-year-old brother Al-Musta’li on the throne, knowing that he could control the latter.

This usurpation succeeded due to the support of the caliphate’s armies, as well as religious

and court notables who were in thrall to al-Afdal, but Nizar wasn’t going to take it. He fled

to Alexandria, where he was proclaimed Caliph by a Turkic governor.

The population also supported him, and it seemed as though Nizar’s revolt would be a success.

A Nizarist army repelled an attack by the vizier’s troops and even advanced close to Cairo, however al-Afdal marshaled his superior resources and besieged Alexandria, leading to Nizar’s surrender in 1095.

After the death of Nizar

Soon the rightful Fatimid ruler had been imprisoned and executed by immurement.

Most of the Ismaili religious communities in Egypt and Syria eventually came to terms with the succession.

Persian and other adherents in the Muslim east, refused, continuing to support the martyred prince’s house and becoming the independent Nizari.

One prominent figure of the Nizari Ismaili would spearhead their movement and found what would become known as the Assassins’ Order – Hasan-i Sabbah.

Hasan-i Sabbah

Although he was born in a Twelver family in Qom, Iran, at some point around 1050, Hasan had been educated in nearby Rey.

After initially believing the Ismaili doctrine to be heretical, he came into contact with a prominent local Ismaili missionary at 17 and was convinced of the sect’s legitimacy.

To prove his newfound devotion genuine, Hasan swore allegiance to al-Mustansir in faraway Cairo.

He then travelled to Egypt in 1078 and stayed there for three years.

During his time in Fatimid lands, Hasan always favoured Nizar’s faction and acted against

the vizier – at the time al-Afdal’s father – a fact which eventually saw him banished

in early 1081.

Hasan Sabbah and Seljuk Turks

Having been thus expelled, he returned to Isfahan. By this time, the once majestic Abbasid Caliphate had been all but subsumed by the all-conquering Seljuk Turks. These new invaders established a Sunni military empire which stretched from Khurasan to Anatolia, ruthlessly persecuting Ismaili ‘heretics’ as they did so.

In opposition to his new Seljuk overlords, Hasan traveled their empire as a missionary for 9 years, gauging their military strength and formulating a strategy of resistance.

In 1087, the Ismaili firebrand started dispatching other missionaries into the vicinity of a

remote and nigh-invulnerable mountain fortress known as Alamut, located in the area just

south of the Caspian Sea, to ‘Ismailize’ its population.

He withstood numerous Seljuk attempts to stop his underground activity and managed to remain in hiding.

Capture of Alamut Castle

In late 1090, Hasan moved via mountainous routes, finally slipping into Alamut unnoticed. He lived under the radar as a religious tutor known as Dihkuhda for several months, instructing the children of Alamut’s garrison and slowly turning prominent figures to his side.

Eventually, the castle’s governor realised the infiltration, but it was too late. He had been slowly surrounded by a garrison and population who supported Hasan.

Incapable of defending himself, the governor left the castle.

Alamut’s capture was the beginning of what would become known as the Nizari Ismaili State,

and the beginning of a new phase in the Ismailis’ relations with the Turkic sultans whom they

vehemently opposed.

What had previously been a clandestine, secret society-like movement became an open revolt aimed at the very heart of the Seljuk state, driven by a mix of sectarian and Iranian ethnic motivation.

Alamut and Seljuk Turks

Sultan Malik-Shah I and vizier Nizam al-Mulk were keen to extinguish this budding heresy, and launched several attacks against Alamut, but the castle held out against overwhelming military strength.

On the contrary, the Nizaris acquired a second enclave of territory in Quhistan after dispatching

missionaries to that area.

They got a break from the attacks in late 1092, when both the sultan and his anti-Ismaili

vizier died. It is possible that Nizam al-Mulk was the very first victim of the Nizari assassins,

though the evidence is tenuous.

Regardless, the loss of these two plunged the Seljuk empire into civil war, essentially fragmenting it into a mosaic of squabbling fiefs ruled by religious and military leaders.

Alamut on the rise

Hasan consolidated his position and expanded Ismaili influence, acquiring other formidable

strongholds in the Elburz mountains, among them Girdkuh and Lamasar. Rather than being

one contiguous state, the various citadels of Hasan’s fortress network were almost always surrounded by potentially hostile territory.

Therefore, the disunited Ismaili mountain castles acted both as an impenetrable defensive

bastion and a base of operations for religious and military activity.

These eastern Ismaili supposedly received congratulations and a message of goodwill from Fatimid caliph al-Mustansir, but after his death and the great Ismaili schism, Hasan cut all ties with Egypt.

Although the Seljuk Empire’s post-Malik Shah weakness removed the immediate threat

to Hasan’s Ismaili realm, the decentralization also made his ultimate goal – the total overthrow

of the Seljuks – almost impossible.

There was no longer a single figure who could be defeated in battle and cast from the throne.

In effect, there was now no central target, but a whole gallery of petty kings.

Please continue reading on the next post:

All the credit of this post belongs to the following youtube post:

https://youtu.be/vG8qmlKdRjs

I am Hosein Farhady, a specialized guide for the Assassins Castles and the history of the Ismailis in Persia.

If you are ready to book an Alamut Tour with me, you only need to touch the whatsapp or email icon at the bottom of this page. Or go to the contact us page.